Why Your HYROX Training Is Probably Too Hard

As HYROX continues to grow, a wide range of athletes are transitioning into the sport. With any rapidly growing discipline, training methods tend to lag behind the actual performance demands. HYROX is no exception.

While the sport is highly accessible and offers enormous benefits across demographics, many athletes are training in a way that limits, rather than enhances, race-day performance.

HYROX Is an Endurance Event - Not a Max-Strength Test

Despite the functional strength elements, HYROX is fundamentally an endurance event.

Elite athletes finish in under 60 minutes.

Most age-group athletes take 90–120+ minutes.

That places HYROX firmly in the same duration category as a Sprint Triathlon, not a CrossFit-style short-duration power event. Even the opening 1 km run sits squarely within the aerobic endurance domain.

If most of your training is built around repeated high-intensity, near-maximal efforts, you are likely compromising your ability to perform across the full duration of the race.

The "Gym Strong" Trap: Why You Bonked After Run 2

There is a specific, painful experience shared by thousands of first-time HYROX athletes.

You trained hard. You were crushing 45-minute HIIT classes. You felt explosive and strong in the gym. On race day, the adrenaline was pumping, you flew through the first 1km run, and you dominated the Sled Push.

Then, somewhere around Run 2 or the Sled Pull, Suddenly, your legs felt like lead. Your heart rate wouldn't come down. The remaining 70 minutes of the race became a survival shuffle. You were left wondering: "I’m fit. I train hard every day. Why do I feel completely flat on race day?"

In the gym, most "hard training" consists of short, high-intensity bursts followed by rest (even short rest). In that environment, your Anaerobic System shines. You can express massive power for 45–90 seconds, recover, and do it again.

But HYROX doesn't offer recovery. It is continuous workout.

When you train exclusively with high-intensity, "red-line" efforts, you teach your body to burn sugar rapidly (Glycolysis) leading to a sharp rise in lactate. The "flatness" you felt wasn't a lack of effort; it was metabolic failure. You had the strength, but you lacked the aerobic infrastructure to support that strength for 90 minutes and you were forced to slow down to an intensity where the body can combust the lactate for fuel.

The Physiology That Actually Limits Performance

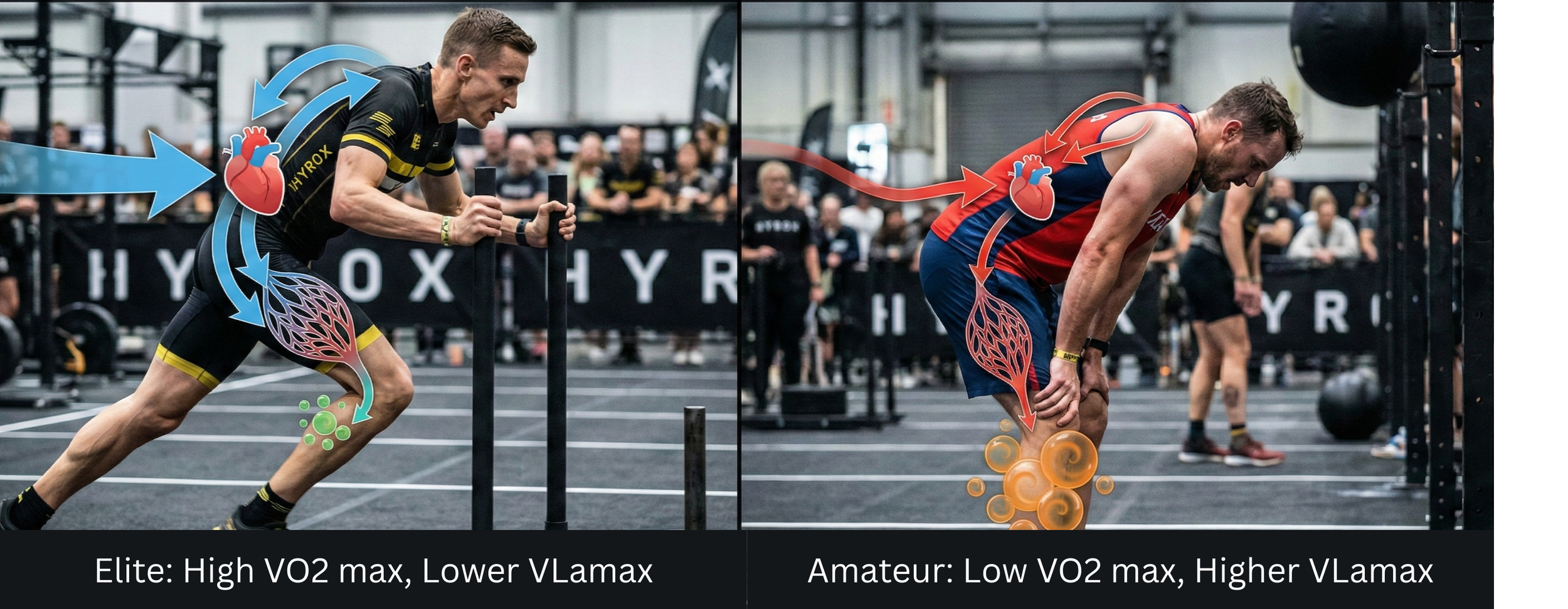

HYROX performance is dictated by the interaction of two key energy systems:

The Aerobic System: Governed by VO2max and movement efficiency. It is responsible for sustaining work and clearing metabolic byproducts.

The Anaerobic / Glycolytic System: Governed by VLamax (maximal lactate production rate). It is responsible for short, high-force outputs.

The balance between these systems defines your Threshold (often referred to as anaerobic threshold or FTP). This threshold determines the fastest pace you can sustain without progressive fatigue.

A Useful Analogy: The Bathtub

The Tap (Glycolytic System): The rate at which lactate is produced.

The Drain (Aerobic System): The rate at which lactate is cleared.

Threshold: The point where the flow from the tap equals the capacity of the drain.

This explains the "Run 2 Crash": Your high-intensity training installed a massive "Tap" (high VLamax). You produced lactate faster than your "Drain" (Aerobic system) could clear it. By the second run, your bathtub overflowed, and your muscles slowed you down / forced you to recover.

Why Too Much High-Intensity Work Backfires

Repeated maximal or near-maximal efforts preferentially develop Type IIa and IIx muscle fibres. While this improves force and short-term power, it also:

Increases VLamax.

Accelerates lactate accumulation at any given pace.

Lowers sustainable race intensity.

The result is the athlete who can hit impressive speeds in training intervals but cannot reproduce them on race day without blowing up. The issue is not a lack of speed; the issue is insufficient aerobic dominance.

How to Fix It: Shift the System in Your Favour

Improving performance means shifting the physiological balance. You can do this by:

Increasing VO2max (raising the aerobic ceiling).

Improving Efficiency (running economy and station technique).

Reducing VLamax (lowering lactate production rate).

While individual priorities vary, aerobic development underpins all three.

Strategy 1: Lift the Aerobic Ceiling (VO2max)

VO2max training should be targeted, not random. The type of interval work that produces the greatest adaptation is strongly influenced by an athlete’s muscle fibre profile and training history.

For Athletes from Explosive / Power Backgrounds

Athletes transitioning from CrossFit, team sports, or strength-power disciplines typically present with a higher proportion of Type IIa and Type IIx fibres. These fibres are capable of high force but fatigue quickly.

For these athletes, improvements are best achieved through shorter, higher-intensity intervals that rapidly elevate oxygen demand without excessive muscular fatigue.

The Approach: Short work intervals (20–40 sec) with very short recoveries.

The Intensity: ≈ 3 km race pace or slightly faster.

Example Session:

3 sets of (10 × 30 sec Hard / 15 sec Easy)

3–4 minutes easy recovery between sets.

This format maximizes time at or near VO2max while respecting the fatigue characteristics of Type II-dominant athletes.

For Athletes from Endurance Backgrounds

Runners entering HYROX typically have a higher proportion of Type I fibres, possessing strong fatigue resistance. These athletes often struggle not with reaching VO₂max, but with spending sufficient time there to trigger adaptation.

For this group, VO2max is more effectively developed using longer intervals at slightly lower intensities.

The Approach: Longer work intervals (2–5 min) with short-to-moderate recoveries.

The Intensity: ≈ 5–10 km race pace.

Example Session:

4–6 × 3 minutes @ 5–10 km pace

2 minutes easy recovery between reps.

This structure allows endurance-trained athletes to accumulate a large volume of quality time near VO2max without unnecessary anaerobic stress.

Strategy 2: Improve Economy and Efficiency

Every improvement in movement efficiency reduces the oxygen cost of work. If you are inefficient, you are "leaking" energy with every step and rep. Improving economy means you can travel at the same speed while using less oxygen—saving your matches for the final stations.

1. Running Mechanics: Stop the "HYROX Shuffle"

As fatigue sets in (usually after the Sleds or Burpees), athletes often drop into a "seated," shuffling running style. This kills efficiency because you lose the elastic return from your tendons.

2. Station Efficiency: Smooth is Fast

Frantic movement spikes your heart rate unnecessarily. Elite athletes look calm because they are efficient.

Transitions: Moving from the run into the "ROX" zone and onto the station is "free time." Don't walk. Jog slowly but purposefully.

Technique under fatigue: On the rower and skierg, losing your stroke length forces you to pull more often to hit the same pace. This drives the heart rate up. Maintain long, powerful strokes even when tired.

3. The Training Fix: Tempo & Threshold Intervals

To improve efficiency, you must practice moving at a speed that feels "comfortably hard" but is sustainable. This is often called Threshold or Tempo training.

You want to train just below the point where your muscles start burning. This teaches your body to clear lactate as fast as it produces it (filling the drain without overflowing the bath).

The Intensity: This should be slightly slower than your open 1 km race pace (approx. 10–15 seconds slower per km). It requires focus, but you shouldn't be gasping for air.

Example Session:

3 × 8–10 minutes slightly slower than your current 10km pace with 2 minutes easy jog recovery

Focus: Holding perfect form and consistent splits while under moderate fatigue.

This type of training builds the "durability" required to keep your running form together when your legs feel like jelly after the lunges..

Strategy 3: Reduce VLamax

This is the most counter-intuitive part of HYROX training, especially for athletes coming from CrossFit or HIIT backgrounds.

Remember the bathtub analogy: VLamax is the tap. If your tap is wide open (high VLamax), you pour lactate into your muscles faster than you can drain it, even at moderate speeds. This is why you feel "the burn" so early. To raise your threshold and go faster for longer, you effectively need to "tighten the tap."

Reducing VLamax doesn't mean you get slower or weaker; it means you become metabolically efficient. You force your body to burn fat for fuel at higher intensities, preserving your precious glycogen for the final push.

1. The Foundation: High Volume Low Intensity (Zone 2)

There is no shortcut here. To lower V̇Lamax, you must spend significant time training at an intensity where lactate production is minimal.

The Protocol: Long, steady endurance work (Running, Rower, BikeErg) at a "conversational pace" (Zone 2).

Why it works: This training volume decreases the activity of glycolytic enzymes. You are literally teaching your body not to reach for the sugar jar as its primary fuel source.

2. Master the "Grey Zone" (Tempo vs. Grinding)

Many coaches tell you to avoid the middle intensity (Zone 3/Tempo) entirely. But in HYROX, you race in this zone. The problem isn't the zone itself—it's how you execute it.

The Mistake (The Grind): Jumping into a "bootcamp" class where you redline, recover, redline, and recover. This is chaotic and highly glycolytic.

The Fix (Controlled Tempo): You need to learn to sit in discomfort without spiking your heart rate.

The Workout: 3 x 10 minutes at "Sweet Spot" (moderately hard).

The Rule: Your heart rate and pace must remain flat. If you have to gasp for air or your heart rate drifts up uncontrollably, you are pushing too hard. This teaches your body to handle moderate intensity using the aerobic system, not the glycolytic one.

3. Rethink Your Strength: Build "Sustainable Strength"

HYROX isn't a 1-Rep Max contest; it's a test of how well you can move weight when you are tired. Traditional "burnout sets" or "max effort sprints" in the gym spike lactate and reinforce the wrong energy system. You need strength that lasts.

The Goal: Move moderate-to-heavy loads consistently without "blowing up."

The Protocol: "Aerobic Strength" Intervals.

Example: 10 minutes of Sled Push (do 30 seconds of work, 30 seconds rest).

The Key: You should be able to maintain nasal breathing or controlled breathing throughout. If your legs start burning intensely, slow down. You are training your Type II (strength) fibers to work aerobically. This builds the durability you need for the Sleds and Lunges without taxing your VLamax.

4. Low Cadence / High Torque Training

Using a bike or Skierg, performing intervals at a low cadence (e.g., 50–60 RPM on the bike) forces recruitment of Fast Twitch fibers but demands they work aerobically because the movement rate is slow. This helps convert Type II fibres to Type I fibres and overtime improve your aerobic engine allowing to your increase volume, improve endurance power and not slow down.

The Key Takeaway

If your HYROX training feels brutally hard all the time, that is likely the problem.

HYROX rewards athletes who can sustain work, resist fatigue, and maintain pace deep into the race. If you felt flat in your last race, it wasn't because you were weak—it was because you were inefficient.

Build the aerobic engine first. Strength and intensity should support endurance, not sabotage it.